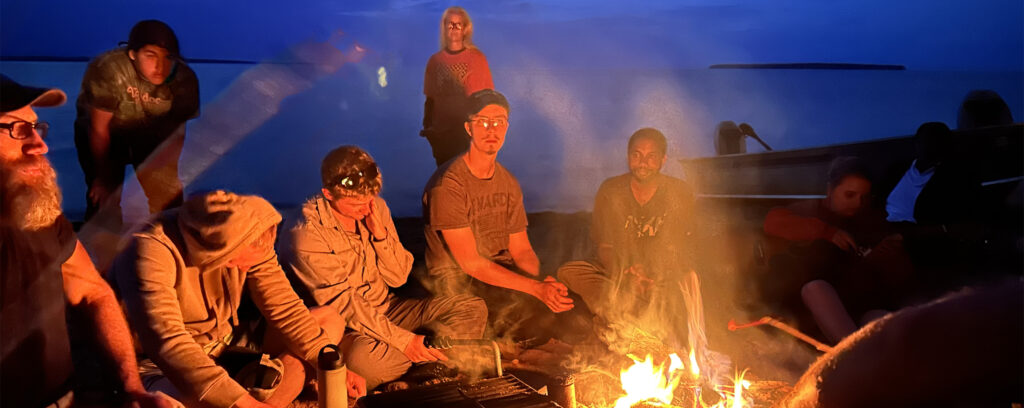

Students on a field study gather on the Lake Superior shore of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Reservation for a bonfire last summer. Some of the undergraduate research projects worked on during the field study were accepted for presentation at the Geological Society of America Conference in Pittsburgh in July 2023 . (Juk Battacharyya photo)

The campfire light dancing on a circle of faces on the Lake Superior shore has a feeling of eternity — as if people have been huddling here for as long as there have been people and fire. Waves lapping at the shoreline keep their own eternal cadence.

In the firelight are five University of Wisconsin-Whitewater students and their professor, Juk Bhattacharyya, professor of geology in the Department of Geography, Geology and Environmental Science. They have been studying the landscape and monitoring the shoreline. Most of all, they have been observing the practices of members of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, located on a reservation that hugs the southern shore of the lake near Ashland, and of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa north of Bayfield.

Projects include topics on indigenous place names as a way to study land, simulating conditions of slope failure, finding sustainable solutions to shoreline erosion and using virtual tours to enhance environmental education.

Measurements from studying shoreline erosion and slope stability will be used by the Bad River reservation’s Mashkiiziibii Natural Resources Department. The beach and shoreline are threatened by both forces of nature and human activity.

“The students went to a tribal member’s house on the beach to monitor how much beach was gone between last year and this year,” said Bhattacharyya.

The data will be used to plan efforts to slow the process, such as establishing plants to make the slope more stable.

The undergraduate research conducted over the summer also resulted in papers that were accepted for presentation at the Geological Society of America Conference in Pittsburgh in October 2023. Traveling with Bhattacharyya to the conference will be geography students Miles McIntosh, Blake Stephens, Dean Wink and Beto Patino Luna and environmental science student Derek Wallis. Students Corban Larson, Jenna Lambert and Ethan Hensel are also co-authors on the projects that will be presented. Bhattacharyya and Ozgur Yavuzcetin, an associate professor of physics, are faculty advisors on the papers.

The students brought disciplines as varied as geology, legal studies, computer science, art, music and business to the projects, and each was given an opportunity to interact as a team and with indigenous culture. The field study was funded by the National Science Foundation’s GEOPAths program, which encourages novel approaches to geoscience.

“The big problems we are facing today like climate change or natural disasters — no single discipline can address any one of them,” said Bhattacharyya.

She said meeting these challenges will require teams from different disciplines, helped along by knowledge from the past.

“This is not the first time that climate change has been happening on this planet. All of the knowledge that (indigenous peoples) gained was passed down somehow,” Bhattacharyya said. “We need to look at how they addressed these problems and bring it into classrooms along with what we are teaching as part of our conventional science (curriculum).”

One project incorporates tribal names into a map as a means of documenting the change that has occurred since the time of the glaciers.

“The tribal names describe what the place is like or what we can expect or what we would use it for,” said Bhattacharyya. “For example, Oconomowoc means ‘lily pad.’ There used to be lily pads there that the tribes would use for food.”

“Mukwonago means ‘many bears,’” she said. “Those names provide some snapshot on how the environment might have changed from the time of the glaciers.”

Partners from the University of Hawaii at Manoa, Stanford University and UW-Madison are partners with UW-Whitewater in the projects through the GEOPaths grant.

“Making the whole larger than the sum of the parts is the whole idea behind this multiple stakeholder project,” said Bhattacharrya. “And it brings traditional knowledge into classrooms. It gives undergraduate students a cultural immersion.”

Wallis, an environmental science student from Sussex who will be a presenter at the GSA conference, was one of the students on the travel study. Wallis also works as an intern in the UW-Whitewater Sustainability program.

“They (indigenous peoples) have 10,000 years of stories and experiences with a changing world,” said Wallis. “They have ways of thinking that are more sustainable than our own. They know how to live with the land while the land supports them. The biggest takeaway I got from listening to their storytelling was how they look at the hierarchy of nature. The Native American way of thinking is that man is actually on the bottom of the hierarchy because we require all of these other organisms to survive.”

Bhattacharyya is proud that UW-Whitewater students like Wallis will finish their undergraduate degrees with graduate-level research and presentations on their resumes. She tells how she listened with two professors from UW-Madison as her students discussed their projects.

“They (students) started talking about skills they could exchange, tossing ideas back and forth,” she said. “About websites, tribal law, a whole discussion of research.”

“One of the professors was saying this is Ph.D.-level research,” said Bhattacharrya.

“We call it undergraduate research at UW-Whitewater.”

Written by Craig Schreiner | Photos by Juk Bhattacharyya and Craig Schreiner

Link to original story: https://uww.edu/news/archive/2023-09-bad-river-reservation