While the scientists in this story aren’t household names, the research they did and the training they received from UW–Madison helped advance their fields of science and improve the world.

From medicine to ecology, engineering to computer science, the University of Wisconsin has for 175 years made valuable innovations that help people and communities across the state and beyond. And today, with one of the highest-ranked research programs in the country, the University of Wisconsin–Madison is well-known for making important scientific discoveries.

But what about some of the lesser-known scientists, often overlooked in their time, who helped make the key discoveries that gave rise to this reputation? Science is a team effort, even if that isn’t always reflected in the history books. While these scientists aren’t household names, the research they did and the training they received from UW–Madison helped advance their fields of science and improve the world.

In recent years, University Archives, the Public History Project and others have worked to highlight some of these people and make up for lost time.

Below are just a few of the scientists from UW–Madison who deserve to be recognized for the contributions they made to Wisconsin and the world.

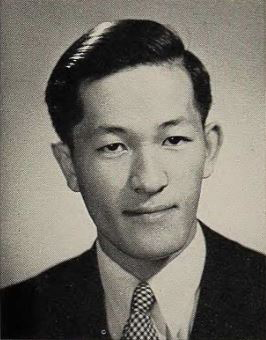

Miyoshi Ikawa

Miyoshi Ikawa

While most people may not have heard the name Miyoshi Ikawa, they probably have heard of warfarin, the medicine commonly used as a blood thinner.

The story of warfarin, which was patented in 1947, began at UW–Madison in 1933, when a farmer sought the help of biochemistry professor Karl Paul Link. The farmer’s cows, who were eating sweet clover hay, began mysteriously dying from internal bleeding. The animals’ blood wasn’t clotting, so Link and his research team decided to find out why.

Once they discovered the chemical compound responsible for the cows’ thin blood, the researchers worked in the lab to create new variations of the substance, each with slight modifications to its chemical structure. Their goal was to maintain the compound’s blood-thinning effect.

Ikawa, a graduate student in the Link lab, fellow lab member Mark A. Stahmann, and Link together created analogue 42, the version that would become what we know today as warfarin. The researchers found the compound was useful as a rodenticide. Later, they discovered it could also be used as a drug to help people with blood-clotting disorders, a pivotal discovery that has saved countless lives.

Ikawa’s contributions as a graduate student at UW–Madison are an important part of the university’s history, though his studies here were linked to a darker part of our nation’s past.

In the wake of the Japanese military’s attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, anti-Japanese racism was rampant in the United States. Ikawa was studying at CalTech in 1942 when President Roosevelt passed Executive Order 9066, declaring the U.S. West Coast a military zone and authorizing the forced evacuation and incarceration of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans. With the help of his CalTech graduate advisor, Ikawa was able to relocate to Madison, Wisconsin, and find a position in Link’s lab where he could continue his education.

Ikawa’s time at UW–Madison not only contributed to the discovery of the famous blood thinner, it also allowed Ikawa to pursue a successful academic career. After finishing his graduate studies at UW, he returned to the West Coast for post-graduate research at CalTech and UC Berkeley and later spent 20 years as a professor at the University of New Hampshire.

Sister Mary Kenneth Keller

Sister Mary Kenneth offers instruction to R. Buckminster Fuller at Clarke College in this undated photo from the mid-twentieth century. Photo Credit: Clarke University Archives

The first woman in the country to graduate with a PhD in computer science was a UW–Madison grad — and a nun.

In 1932, at 18 years old, Mary Kenneth Keller entered the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Soon after taking her religious vows, Keller began a teaching career in in Illinois and Iowa. During summer break, she attended DePaul University and earned her bachelor’s degree in mathematics in 1943. Nearly 10 years later, she also earned her master’s degree.

Keller was teaching high school math on the west side of Chicago in the early 1960s when she began to realize the rising importance of computers as a tool in mathematical computation. Intent on learning more, she attended a summer program at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, where she and other high school teachers learned how to operate computers and write simple programs.

Later, when Keller was in her fifties and teaching math during summer school at Clarke College, the school’s president decided to send her to UW–Madison to pursue a PhD in computer science.

In her dissertation, “Inductive Inference on Computer Generated Patterns,” Keller explored the ways computers could be used to mechanize tasks and solve problems.

After earning her PhD from UW in 1965, Keller established the computer science department at Clarke College and gave lectures on computer science at other institutions whenever she could.

She was an avid proponent for women seeking higher education and for working women in general, especially mothers. She was even known to encourage her college students to bring their children to class.

Marguerite Davis

There once was a time when people didn’t worry about taking their vitamins … because no one knew what vitamins were. Then, beginning in the 1910s, our understanding of nutrition changed, thanks in part to the dedication and careful observations of Marguerite Davis.

Davis, a Wisconsin native, grew up inspired by the women’s rights movement in the late 19th century. She also had an interest in science and began pursuing higher education at UW–Madison before transferring to the University of California to complete her bachelor’s degree. Called back to Wisconsin to help look after her father’s house, Davis went in search of ways to continue pursuing science.

Enter: Elmer McCollum, a professor in the Department of Agricultural Chemistry at UW–Madison. In the early 1900s, McCollum was attempting to create a simple mixture with exact quantities of proteins, carbohydrates and fats that could replace the standard feed given to animals and optimize their diets. But so far, the animals fed on McCollum’s experimental diet experienced stunted growth, sickness and even blindness. Something was missing.

With Davis’s help, McCollum began tedious and time-consuming studies to uncover what was that something was. In a study focused on the role of different kinds of fats on growth, Davis helped feed, care for and take detailed observations of the rats they used in their model.

Some rats were fed a dairy-based fat while others were fed olive oil or lard. The rats fed oil or lard became sick and failed to grow properly, but those who consumed dairy fat continued to grow. Realizing there must be important compounds in the dairy fat, McCollum and Davis extracted those compounds and added them to the oil and lard.

Their hypothesis was confirmed when rats fed the fortified oil or lard were as healthy as those fed dairy fat. In 1913, McCollum and Davis were both listed as co-authors in the paper describing these findings, identifying the important compound as fat-soluble A, or, what we now know as vitamin A.

Since animals don’t drink milk their whole lives but still grow and develop, the scientists guessed that other foods must also hold these vital nutrients. Davis and McCollum launched into subsequent experiments to find these foods and to understand the benefits the nutrients gave to animals, and later, humans.

Each year Davis worked in the lab, McCollum requested a salary for her, but it wasn’t until her sixth year that he actually received the funding. Despite not being paid for those six years, Davis continued to make vital contributions, changing the field of nutrition as we know it.

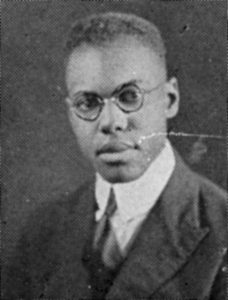

Leo Butts

Leo Butts in his senior yearbook picture in 1920.

Leo Butts was the first known African American to study at and graduate from the UW School of Pharmacy. Butts grew up in Madison, and by the time he was in high school, he was very involved in activism for civil rights.

He graduated from high school in 1917 and enrolled at UW–Madison. On campus, he became the first African-American to play for the varsity football team, and he enlisted in the Students’ Army Training Corps.

But arguably his most important accomplishment while at UW–Madison was his senior thesis, “The Negro in Pharmacy.” Butts pieced his thesis together despite having limited documents, records and literature with which to work. Though the libraries at UW–Madison had a host of information and resources on pharmaceutical studies, very little of it pertained to African Americans’ role and relation to the field.

Driven by his desire to learn more about Black influence in his chosen profession, Butts sought research sources elsewhere by reaching out to prominent African American pharmacists and pharmaceutical organizations of the time. Though the details he gleaned from these correspondences were limited, he was able to collect anecdotes and statistics on the number of existing African American pharmacists and drugstores.

In his thesis, he also demonstrated the benefits of increased cooperation between African American doctors and pharmacists: improvements in the health of African American communities and their sense of connection.

After graduating, Butts and his fiancée Alice moved to Gary, Indiana where they were married. Butts passed the Indiana State Board exam and began working as a pharmacist. He lost his job as a pharmacist during the Great Depression, though he worked for a time as a mail carrier for the U.S. Postal Service. Eventually, he returned to his chosen profession, owning and operating a pharmacy until he passed away in 1956. It was here that he provided both care and a place of gathering for his community.

Unfortunately, the lack of easily available information on African American pharmacists seems to have persisted into the 1980s, when James Buchanan, who graduated from the School of Pharmacy in 1943 as its second known African American graduate, found himself wondering if he had been the first student do so.

Eloise Gerry

Elouise Gerry in her laboratory, about 1936.

The nation’s first woman microscopist was also a UW–Madison graduate and professor. Eloise Gerry first moved to Madison in 1910 to join the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s then-new Forest Products Laboratory. The mission of the lab was to identify and conduct innovative wood and fiber use research that contributed to the sustainability of forests.

While working with the Forest Products Laboratory, Gerry also continued her education, studying botany and plant pathology and eventually earned her PhD in 1921. Later, she became a professor at UW–Madison.

At the start of her career, Gerry specialized in identifying and cataloguing the anatomical structure of trees. By 1916, she became motivated to help conserve pine trees in the American South and began her own research program.

Traveling around the American South collecting data, Gerry showed that the lumber industry was cutting down pine trees at an unsustainable rate. Not only was overlogging affecting the longevity of the ecosystems, it was also contributing to the struggles of businesses and the economy built around pines.

Thanks to the samples she collected and analyzed, Gerry’s research helped stabilize the industry.

Historical anecdotes recount Gerry’s pride as a woman in her field. When she was first hired at the Forest Products Laboratory, she recalled that “there wasn’t any man willing to come and do the work.” After earning her PhD, she was sure to sign her full name, “Dr. Eloise Gerry,” rather than just her first initial and last name so that people would know she was a woman.

She even served as the president of Graduate Women in Science, a global organization that still works today to build community and to inspire, support, recognize and empower women in science. The organization also established a fellowship in Gerry’s name that continues to offer research funding to selected fellows.

Gerry was also recognized for her dedication as a member of the American Chemical Society, the Society of American Foresters and the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Despite these recognitions during her career, her contributions to the study of southern pines and importance as a woman in science are not widely known today.

Written by Elise Mahon

Link to original story: https://news.wisc.edu/surprising-contributions-from-uw-madisons-overlooked-scientists/