UW-Stout Professor Tom Lacksonen and Hastings Mkwandwire, a resident of Mzuzu, Malawi, observe one of Mkwandwire’s hand-built hydroelectric generators under a metal covering.

Electricity could become a reality for more homes in a city in northern Malawi, Africa, because of a University of Wisconsin-Stout professor’s research and resourceful students’ problem-solving skills.

Tom Lacksonen, an operations and management professor, traveled to the mountainous city of Mzuzu in January with manufacturing engineering and computer engineering student Josh Miller. Their mission: to gauge whether a student-designed prototype for a minihydroelectric generator could be economically mass produced there with available resources.

While the city receives some hydroelectric power from power stations on the Shire River, power cuts and rationing often affect the supply. Mzuzu’s rural settlements have little or no access to electricity. Streams winding through the mountains and jungles provide an ideal power source for hydroelectric generators, which use concentrated pressure and water flow to turn turbines or water wheels to drive an electric generator.

Rural homes in Mzuzu, Malawi, receive electricity from generators built by resident Hastings Mkwandwire, who participated in a U.S. leadership program at UW-Stout.

Lacksonen and Miller discovered that the original prototype required parts that would be difficult to find and make on a large scale there.

“They weren’t able to manufacture our first design, so we were forced to redesign,” Lacksonen said.

For about a week, Lacksonen and Miller worked with Mzuzu resident Hastings Mkwandwire and his team to develop a simpler, more efficient model that would be easier and less expensive to produce.

Lacksonen met Mkwandwire when the young scholar came to UW-Stout in summer 2014 for the Young African Leaders Initiative. Established by President Obama, YALI empowers young African leaders through academic coursework, leadership training, mentoring, networking, professional opportunities and support for activities in their communities. UW-Stout has been chosen to host YALI scholars for the past three summers.

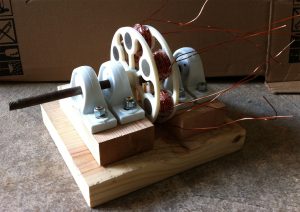

In a rented garage, Mkwandwire had been building hydroelectric generators out of available scrap parts. Three of his generators currently power up to 10 homes.

Sandcasting, 3D printer refine model

Since receiving the UW-Stout Andrew G. Schneider Professorship to bring global issues into the classroom, Lacksonen has been using student product and factory designs to enable YALI participants to mass produce products in their home countries.

UW-Stout student Josh Miller, who graduated in May, built a new prototype of a minihydroelectric generator using one of the university’s three-dimensional printers.

As part of an independent study, Miller’s task was to create a second prototype. He had to be prepared to make trade-offs when designing the hydroelectric generators and designing a manufacturing facility in Malawi versus the U.S.: whether it was possible to use available scrap material to create a consistent product and how to make necessary changes to create a safe work environment there.

Solving the problems onsite was an invaluable way to see the challenges firsthand, Miller said.

“Someone could plan and design a system, machine, or product for weeks until it appeared perfect, but if the manufacturing constraints were not fully understood or laid out properly, it would not be a success,” he said.

“This project had no shortages of challenges,” Miller said. “The hardest part was probably being away from UW-Stout and all of its resources. It is amazing how much the labs at UW-Stout aid in the rapid prototyping and development of ideas and how much a person can miss being in walking distance to it all.”

Back at UW-Stout after the trip, Miller designed a new working prototype using the university’s three-dimensional printer in its 3D printing lab. Sandcasting would produce key components with minimal resources. In sandcasting, a sample part is pressed into sand and removed, leaving behind an imprint of the part. Molten aluminum is poured into the cavity. The aluminum cools into the shape of the original part.

“Sandcasting of 3D printed forms allow precision manufacturing without any tools,” Lacksonen said. “The only parts they would purchase would be copper wire and bearings. Everything else would be scrap metal.”

The final generator would be about 1 foot long, wide and high, with a turbine on the end of the shaft. Water turns the turbine, which rotates the shaft containing a set of magnets. The magnets pass in front of a series of copper coils, which produce electric current in the coils.

Most funding for their travel and expenses came from the professorship, funded through the Stout University Foundation, and a Student Research Grant through the Office of Research and Sponsored Programs.

Since graduating in May, Miller, of New Richmond, has been a software developer for Marshfield Clinic Information Services.

End result hinges on future help

In order to finish the humanitarian project, undergraduate students will need to make and test sandcast parts and rewire the new prototype with electromagnets rather than expensive rare earth magnets, reducing the cost of one kilowatt unit from $80 to $40. A team of four engineering technology students will tackle those issues this semester. Alumni with expertise in specific areas would help move the project forward.

“We’re hoping to get back to Malawi,” Lacksonen said. “We definitely need someone with sandcasting knowledge who can help them install and train them in a sandcasting facility, as well as an electrical engineer to look over our design.”

If the new prototype can be produced, a church in Mzuzu has offered to install and maintain the generators. Each would power about five homes.

Support from multiple entities has been inspiring, Lacksonen said. “This is a great project on many, many levels.”

Hastings Mkwandwire and other village residents experimented with ways to build generators. UW-Stout student Josh Miller, left, later built a new prototype. Miller and Professor Tom Lacksonen, third from left, visited Malawi in January.