Britta Larson from UW-Superior was one of four students who did field work in Door County.

A Freshwater Collaborative for Wisconsin grant helped students from six UW campuses train at one of three locations of UW Oshkosh’s Environmental Research and Innovation Center

When Amanda Stickney learned about chemistry in sixth grade, her love of math and science clicked.

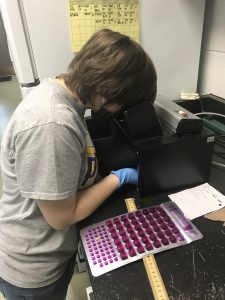

Amanda Stickney analyzes samples at the ERIC lab.

“In high school, I went to a semester boarding school that focused on environmental science and stewardship,” says the recent graduate of UW-Stevens Point’s chemistry program. “That’s when I knew I wanted to do something with environmental chemistry.”

Last summer, Stickney had a unique opportunity to expand her laboratory skills at UW Oshkosh’s Environmental Research and Innovation Center (ERIC), the UW System’s most comprehensive research and testing center. Each year ERIC hires about 40 students for its various programs. Historically, most of them have been undergraduates from UW Oshkosh.

A grant from the Freshwater Collaborative of Wisconsin (FCW) helped give students from other UW campuses, including UW-Eau Claire, UW-Stevens Point, UW-Stout, UW-Superior, UW-Parkside and UW-Whitewater, the opportunity to train at one of ERIC’s three locations — Oshkosh, Manitowoc, or Door County. The FCW grant funded four positions, and an additional three-and-half positions were funded through matching grants.

“We provide opportunities for students to learn the techniques, the workflow and the environment of this type of laboratory,” says Greg Kleinheinz, Viessmann Chair of Sustainable Technology and professor of environmental engineering technology at UW Oshkosh. “One of the goals of our Freshwater Collaborative project was to make inroads with other campuses and bring students from the different campuses together.”

Students spent a week in the ERIC lab training and learning analytical techniques. Because of her major, Stickney worked in the lab all summer, learning how to run the equipment, analyze samples and follow standard operating procedures.

“If I want to work in a lab, I wanted to really learn chemical safety,” she says. “Not everyone can follow an SOP [Standard Operating Procedure] for how to run a test or make a chemical.”

Being a chemistry major, Stickney also appreciated the opportunity to learn more about biology and microbiology. That knowledge will help her succeed at Ohio State University, where she began the master’s in environmental science program this fall.

Britta Larson (top photo), a biology and chemistry major at UW-Superior, was one of four students who did field work in Door County. They tested beaches for coliforms, E. coli, microcystin and microplastics; looked at parameters that could influence bacteria levels at the beaches; assisted in method development for finding and analyzing the microplastics; and analyzed the safety of drinking water.

Jason Trzebiatowski from UW-Eau Claire

“This program was very field heavy, and it taught me that conditions are variable and to be prepared to problem solve. This also helped me to notice what type of career I would like,” says Larson, who plans to go to graduate school for water resource management or natural resource management.

Both Larson and her teammate Jason Trzebiatowski, a biology major and pre-professional medicine minor from UW-Eau Claire, say one of the highlights was learning how to run and manage a field laboratory.

For Peyton Maki, a senior environmental science major at UW Stout, the hands-on experience provided insight into his career path. His current post-graduation plan is two years in the Peace Corps, where he hopes to practice the skills he learned over the summer, followed by graduate school.

Peyton Maki from UW-Stout

“By participating in this internship, I think I have largely increased my skill for both field and lab work, as well as learning my passion for the work I have done this summer,” he says. “It has let me get a better understanding of some of the tasks I will need to solve and work in for a future job.”

Kleinheinz says the program has exceeded expectations — and response to the FCW-funded positions was so strong that UW Oshkosh hired 20 additional students for a different program that studies invasive aquatic species in Vilas County.

Beyond the student experiences, the ERIC program is fulfilling another goal of the Freshwater Collaborative: connecting UW System faculty. Kleinheinz says when they reached out to UW Stout to discuss the ERIC program, the conversations snowballed into additional collaboration to develop common coursework and certificates. And this past summer, faculty from UW-Eau Claire brought a field class, also funded by the FCW, to visit the ERIC students and study water resources in Door County.

“The students are an easy way to make introductions between the faculty,” Kleinheinz says. “Faculty are busy, but when they see how an opportunity directly benefits their students, they start to see how they can do other collaborative things. That starts to build those faculty connections, and that will grow into future students research opportunities.”