The Feast of Crispian is a program at UW-Milwaukee that helps veterans find a way to express themselves through the words of William Shakespeare. UWM educates more military veterans than any other four-year college in Wisconsin.

Charlie Walton has been searching for the words since the moment he touched down in Vietnam as an 18-year-old Marine. After a trans-Pacific flight filled with gung-ho songs from boot camp, a Viet Cong sniper welcomed Walton and his fellow recruits by picking off a lieutenant as he deplaned. On his first patrol, Walton was attacked by a North Vietnamese soldier brandishing a knife. Walton froze and couldn’t pull his rifle’s trigger. His squad opened fire, and the assailant fell at Walton’s feet. Later, a friend stepped on a land mine. Legless and begging for help, he bled to death in Walton’s arms.

Walton didn’t speak of such things, and so much more, for decades. How could he? When he came home, no one wanted to hear about it. He lost touch with his brothers in arms. He lived alone with the nightmares and guilt. He turned to drugs. He went through six wives and countless jobs. Then, about 15 years ago, a friend urged him to seek help at the Clement J. Zablocki Veterans Affairs hospital in Milwaukee. Walton screamed, vented, pleaded and cried to therapists and social workers, and it released much of the pressure. But he still couldn’t open up to the world. He couldn’t find the words.

That’s when a VA social worker directed him to a new program with University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee roots. There, veterans had found a way to express themselves through the words of someone else: William Shakespeare. It was called the Feast of Crispian, after the famous call to arms in Shakespeare’s “Henry V.” The idea was to turn veterans into thespians, allowing them to make the Bard’s dramatic dialogue their own.

“It helps me express myself,” Walton says. “I was brutal to people, the things I could do and say. The Feast teaches me to transform that energy. It teaches how to be angry and sin not.”

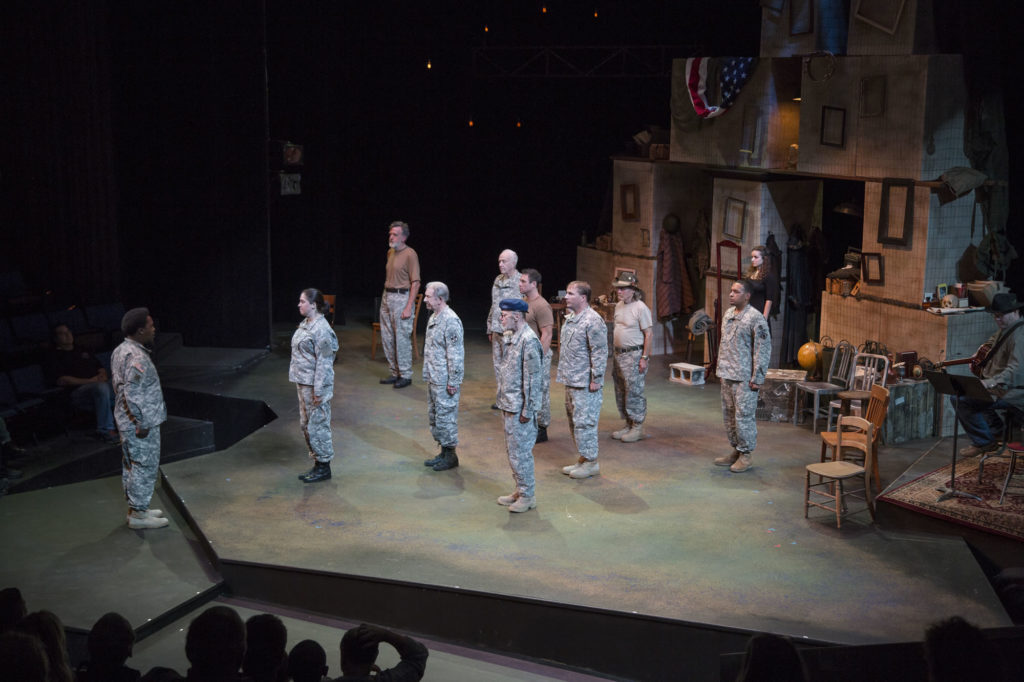

Feast of Crispian was created by Nancy Smith-Watson, Jim Tasse and Bill Watson. (UWM Photo/Troye Fox)

Feast of Crispian is the brainchild of three people: Bill Watson, a UWM associate professor of theater; his actress/somatic therapist wife, Nancy Smith-Watson; and Jim Tasse, a UWM theater senior lecturer and military veteran. UWM educates more military veterans than any other four-year college in Wisconsin, and the trio was looking for a way to combine their skills to help people.

They’d seen how Shakespeare had been used in Massachusetts prisons to help inmates and focus wayward juvenile offenders. Why couldn’t the same method help men and women suffering from post-traumatic stress, which so plagues veterans that every day, on average, 22 of them commit suicide?

“As an actor,” Tasse says, “when doing Shakespeare, you’re tapping into an energy. We’re taking that energy and tapping into a veteran’s story, and allowing it to be released.”

In some instances, the results have been nothing short of life-saving. “I never thought I would live to see my 40th birthday,” says Carissa DiPietro, an Army veteran who was raped by a noncommissioned officer. “I always thought I would have committed suicide by then. But thanks to Feast of Crispian, I’m now 41, and I have my whole life ahead of me.”

Feast of Crispian’s work isn’t meant to replace other forms of therapy, but for many veterans, it has served as a valuable supplement.

“Conventional therapy, where you go directly into the traumatic memories, wasn’t working,” Bill Watson says. “It just retraumatizes them. So how can you access it obliquely? Your target as an actor is to try to get in touch with an emotion that is supposed to have happened. To buy into it enough that you tap into your own grief. We’re working on getting emotionally connected for real into something that is imaginary.”

In 2013, the Crispian co-founders put their theory into practice. They partnered with the Zablocki VA to hold weekend workshops at the hospital. They chose scenes centered on direct interpersonal conflict, usually between two or three actors, from plays that dealt with war, like “Henry V,” “Julius Caesar” and “Othello.” The workshops attracted a dozen or so ex-service people of every age, from Vietnam vets to combatants in Iraq and Afghanistan. Five years later, the method remains the same.

Vets gather and sit in a circle. On Friday, roles are assigned, with Saturday reserved for rehearsals. They play out scenes in the middle of the circle, the professional actors hovering over their shoulders like guardian angels, whispering lines into their ears. The vets are then free to focus their emotions and soak in the experience without the burden of memorization. When a line isn’t said quite right, Tasse, Watson or Smith-Watson will coax a different delivery through a simple remark: “He just called you a liar. How does that make you feel?” The line is spoken again, and the scene continues seamlessly. Then, on Sunday evening, the groups perform for the public.

“You take your own skin off and put someone else’s on,” says Ronnie Graham, a UWM theater student who served in the Navy and now helps run the group as a liaison. Working with Feast of Crispian has helped him through his own difficulties with substance abuse brought on by his wife’s death from leukemia. “You can say things and do things, whatever you want, and it’s therapeutic. Then you can come back and be yourself without hurting someone. I hurt a lot of people trying to search for something to hold onto to make me happy.”

UWM theater student and Navy veteran Ronnie Graham (front, right) found solace in Feast of Crispian in the wake of his wife’s death.

The interplay also allows the actors to connect with the kindred damaged spirit behind the mask. DiPietro says she feels more comfortable when acting with this crew of like-minded vets than she has anywhere in a long time. “In this group was the first time I told anyone that I had been raped, other than the military police. Before I even told my husband,” she says. “When you’re on that stage, all you have is each other.”

Shakespeare, Graham notes, is ideally suited for this sort of exercise. “It’s amazing that things he wrote about 400 years ago are still relevant today,” he says. “The language is so beautiful.” He believes its rhythm, in the Bard’s iambic pentameter, is therapeutic by itself.

That belies some memories of Shakespeare held by those who dreaded third-period English. But Watson says the biggest barrier is not the heady material; it’s the fear of performing in front of others. “That’s one of the things that drives this, though,” Watson says. “We’re putting them through this stress on purpose.”

Occasionally, the pressure gets a little too real. In a production of “Othello,” one vet-turned-actor was supposed to break up a knife fight between characters. The experience awakened a dark memory from Operation Desert Storm, and a real scuffle might have broken out were it not for the intervention of his surrounding friends. “It sometimes triggers their PTSD,” Watson says. “But it’s in a safe circumstance.”

The practice builds confidence. And, Watson adds, onstage stress is met with positive feedback in the form of audience applause: “They were heard. They were seen. And they were validated that it was OK to expose all that.”

Feast of Crispian has spurred interest from other schools and veterans’ organizations nationwide. A demonstration was staged at a reception during the UW Board of Regents meeting hosted by UWM in summer 2018. The audience’s emotional response was palpable, and in the following days, the program’s leadership received inquiries from colleagues in the UW System who wanted to learn more.

But perhaps the best gauge of Feast of Crispian’s success is the individual growth of its participants. After three years in Crispian, DiPietro now helps facilitate an annual women’s-only weekend for veterans and the wives of Crispian vets so that they can share the experience. “I’ve seen it change marriages,” she says. “I now have a relationship with my husband and my children. And I’m starting to like myself.”

“You see how it eases their transition,” Graham says. “They see that they’re not alone in this world. It’s not just me who has these messed-up thoughts. People have for hundreds of years.”

Charlie Walton has found a kindred soul in Brutus, the antagonist from Shakespeare’s historical drama “Julius Caesar.” Walton is not an assassin; nor is he a traitorous friend. But in Act IV, Brutus and co-conspirator Cassius, now both soldiers, are in the former’s tent before a battle that was sparked by their regicide. The men, facing the deadly consequences of their actions, turn on one another and on themselves. Brutus accuses Cassius of having accepted bribes to kill Caesar, and he tries rationalizing what he’d done for honorable, patriotic reasons.

“Remember March, the ides of March remember,” Brutus says. “Did not great Julius bleed for justice’s sake? What villain touch’d his body, that did stab, and not for justice?”

When Walton first stood in the middle of the room, performing this scene with a 300-pound biker playing Cassius, he was not thinking about the fight for Rome. He was revisiting his own war. As he repeated these lines, Walton unloaded a burden he’d silently carried for 50 years.

“I faced him and he faced me,” Walton says. “It was awesome.”