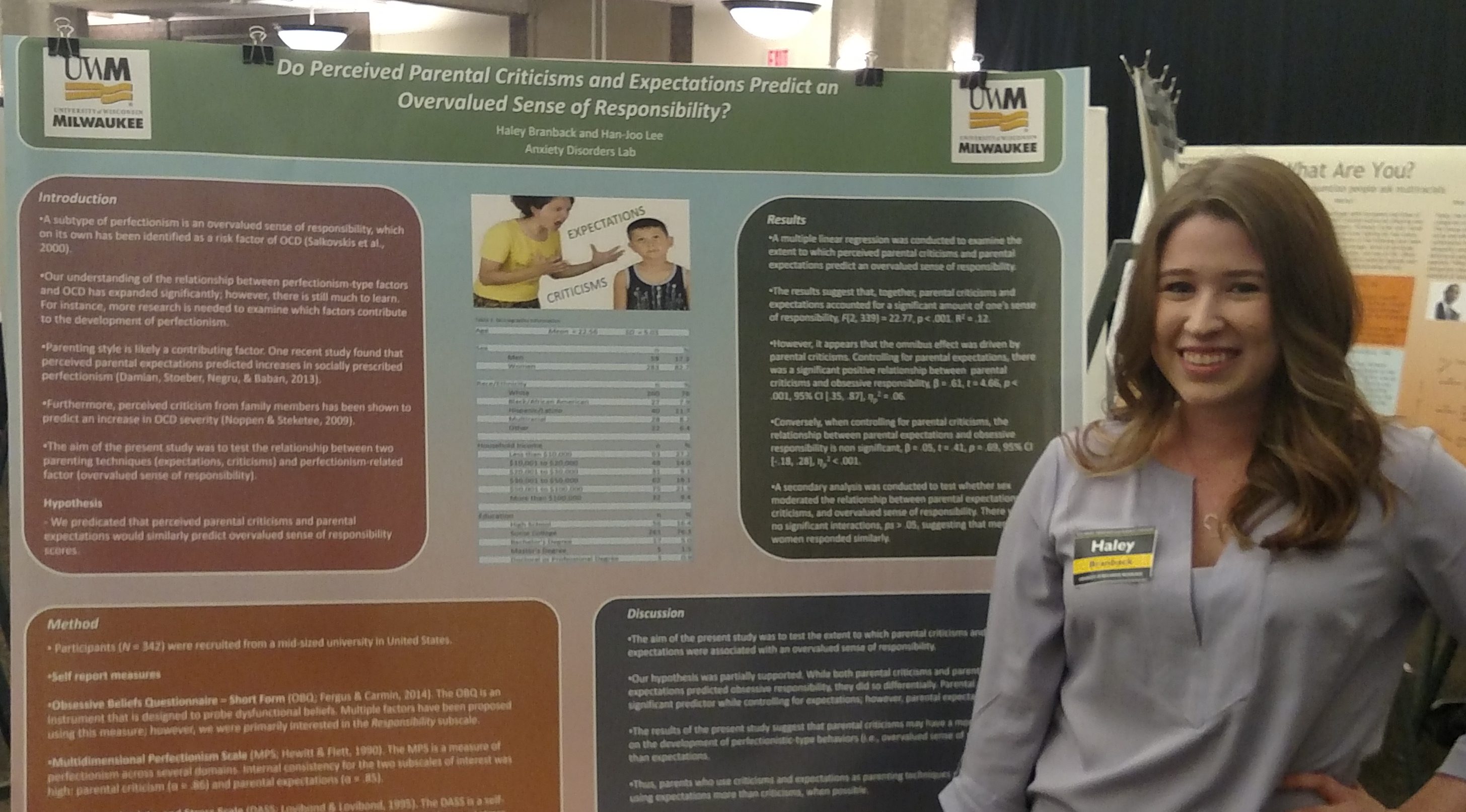

Undergraduate psychology student Haley Branback presented her research on the effects of parental criticism at UW-Milwaukee’s Undergraduate Research Symposium. (Photo courtesy of Haley Branback)

Parents, if you don’t want your child to take life too seriously, lay off criticizing them.

That’s the conclusion psychology major Haley Branback reached as a result of her research examining how parental expectations and criticisms affect their children’s sense of responsibility later in life. She gave a poster presentation on her project at UW-Milwaukee’s Undergraduate Research Symposium this spring.

“I focused on parental expectations and criticisms and how their children perceive them,” Branback explained. “A lot of people came up to me at the poster presentation because they’re parents and they were interested.”

Branback works in psychology professor Han Joo Lee’s lab, which focuses on research into mental health disorders including anxiety, phobias and obsessive compulsive disorder. Branback also works with children, so she combined her work interests and her research to test whether parental expectations and criticisms could lead to an overvalued sense of responsibility in their children.

An overvalued sense of responsibility is a key feature of OCD. It can be highly related to perfectionism and general distress, said Taylor Davine, a UWM psychology doctoral student and Branback’s mentor for the project.

“If I broke a glass and didn’t clean it up very well, and someone got cut, most people would feel a sense of responsibility – ‘Oh, that was my fault,’” Davine said. “But someone who has an overvalued sense of responsibility would go beyond that. You’re always worried that maybe you did something wrong despite a lack of evidence for supporting the idea, and experience strong urges to prevent a possible disaster that would be attributable to you.”

To conduct her research, Branback pulled data from a survey battery from a larger study about OCD. She looked at the results of more than 300 UWM students and examined whether their parents’ expectations and criticisms had any impact on their sense of responsibility.

They did, Branback said. But then she separated expectations from criticisms by controlling for one trait versus the other.

“We actually found that expectations did not lead to an overvalued sense of responsibility, but criticisms did,” she said. Moreover, it wasn’t actually the criticism itself at fault; it was the students’ perceptions of their parents’ criticism that determined whether they had an overvalued sense of responsibility.

“When we recruit students from university, they typically are no longer living with their parents, so it’s really their perception of how they were raised,” Davine said. “We can’t go back and ask their parents if they were critical or if they had high expectations. Even if we did, it may not even matter, because what matters is the way the child perceived the parenting.”

The findings fascinated several judges at the symposium, who were parents themselves. To avoid children developing an overvalued sense of responsibility, Branback suggests, parents should check with their children about how any criticisms are being received. She would like to expand her research and study younger children – perhaps in middle school – to compare children’s perceptions of their parents’ criticism against reality.

“I think with younger children, it can really affect the rest of their career and their path,” Branback said.

Branback herself plans to attend graduate school after she graduates from UWM in December of this year. She hopes to become a school psychologist and draw on her experiences doing research at UWM.

“I think it’s really important to get involved in research. It helps you learn more about psychology, and pursuing your career,” Branback said.